On the 12th anniversary of the Nobel Laureate “Scribe of Cairo” death – his obituary revisited, first penned as obituary on 30 August 2006

The death on 29 August 2006 of Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz generated a quarrel between historians, literary critics and Egyptians on one side, and Arab journalists on the  other. It was a re-run of the 1988 controversy, when Mafouz won the world’s most prestigious award–the Nobel Prize for literature–to the outrage of Arab nationalists who had condemned the author for his support of the late President Anwar Sadat’s peace initiative with Israel.

other. It was a re-run of the 1988 controversy, when Mafouz won the world’s most prestigious award–the Nobel Prize for literature–to the outrage of Arab nationalists who had condemned the author for his support of the late President Anwar Sadat’s peace initiative with Israel.

Last month Egyptian literary circles were outraged again by Arab journalists attempting to claim Mahfouz as their own, describing him in their obituaries as an ‘Arab writer’, while a few years earlier they spared no opportunity to condemn his backing for peace with the Jewish state; support which in 1979 caused Mahfouz’s works to be banned from all Arab countries.

Millions of words have been written about Mahfouz and his works. The late British author and essayist John Fowles (1926-2005) wrote in 1978: “Mahfouz allows us the privilege of entering a national psychology, in a way thousands of journalistic articles or television documentaries could not achieve.” Fowles’ words were among the shortest, yet the most descriptive of the unique craftsmanship of Naguib Mahfouz.

Historically, any phenomenon which emerges in Egypt dominates the area between the Atlas Mountains and the Persian Gulf and, true to form, it is almost impossible to find a single contemporary writer in that area who has not been influenced by Mahfouz.

The author of 43 novels, 11 short stories, 30 screenplays and numerous literary essays and articles, Mahfouz was probably the only original novelist who captured the imaginations of all Arabic speaking peoples; yet at heart and soul he remained Egyptian–rather than Arab or Middle Eastern.

When Arabs banned his work from their countries in 1979, the ‘Scribe of Egypt’ barely noticed; he continued his writing in the mornings, reading in the afternoon, and influencing the many young writers who congregated daily before the master at the ancient cafe in central Cairo that was his ‘local’.

Mahfouz was never a political activist. And, despite a high-level preoccupation with social injustice and oppression, he remained aloof from politics at a time when the vast majority of Egyptian writers joined Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser’s ‘Socialist Union’, the backbone of his Stalinist style, one-party dictatorship; instead Mahfouz let his works speak volumes, reflecting the national spirit of Egypt. Especially in early 1960s, after Colonel Nasser abolished the name “Egypt” . In 1958, Colonel Nasser, without consulting the people of Egypt except in a retrospective rigged referendum , decided to form a federation with Syria naming the country “ The United Arab Republic”, which lasted only two and half years; but the name was stuck until President Sadat restored the name Egypt in 1971. Ironically, nobody referred to the country except by its old name, Egypt; except in official correspondence by die-hard bureaucrats who swelled by 700 percent under Colonel Nasser regime (1054-1970). Mahfouz understood the mood of the people and reflected this deep Egyptianism in his works by drawing a very localised features on the location and charters through their dialogue, physical description or interaction among them.

Spreading his transparent cloak of social criticism to cover the old Egyptian monarchy (1805-1953), the British presence (1882-1956) especially during WWII and the subsequent regimes evoked by General Mohammed Naguib and Col. Nasser’s, 1952 Military Coup Mahfouz’s wry wit could be scathing, and his social satire bit to the bone.

He frequently challenged received pieties, including those of Islam. In 1959, his Children of Gebelawi caused uproar. Critics likened its characters to the main prophets mentioned in both the Bible’s Old Testament and the Koran, to the fury of Islamists. Pressure from Egypt’s (the Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs) of al Al Azhar’s ( roughly the Muslim Church or the  equivalate of Church of England as a source of religious s and moral guidance ) urged the stopping of its publication (all major publishing houses were nationalised a few years earlier by Nasser Regime), but it was serialised in 1960 in the semi-official daily Al Ahram and the book was eventually published in Beirut in 1962.

equivalate of Church of England as a source of religious s and moral guidance ) urged the stopping of its publication (all major publishing houses were nationalised a few years earlier by Nasser Regime), but it was serialised in 1960 in the semi-official daily Al Ahram and the book was eventually published in Beirut in 1962.

The novel was condemned again in 1989 by Sheikh Omar Abdul-Rahman, (currently serving a 15-year sentence for conspiring to blow up the World Trade Centre in New York in 1993), when the late Ayatollah Khomeini issued a death fatwa against author Salman Rushdie for publishing the Satanic Verses in 1988. “Had Mahfouz been slaughtered when he wrote Children of Gebelawi,” said Sheikh Rahman, “Rushdie would have never dared to insult Islam.”

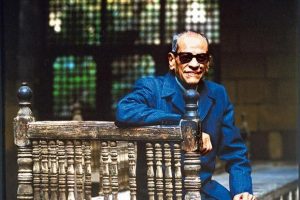

In October 1994, a day after the anniversary of receiving the Nobel prize, Mahfouz was stabbed in the neck by two extremists outside his Cairo home. His life was saved by the quick reactions of a friend, but the attack took its toll, among other things leaving the right-handed author, who only scribed in longhand, unable to write with his right hand.

Commenting on Mahfouz’s death in the London Arabic daily Asharq Al Awsat, Sudanese Islamist opposition leader Sadiq El Mahdi condemned Children of Gebelawi and other ‘philosophical’ works dealing with religion. However, reactions from readers on the paper’s website tell a very different story. While repressive politicians may delight in the Islamists’ blockade against the Mahfouz style of writing, the majority recognise that few writers today would dare to tackle some of the themes he handled between the two world wars.

Many of the characters created by Mahfouz are household names in Egypt and beyond, by millions who regard the characters as their own mouthpieces, expressing indignation, resentment or even hope for a better future. ‘Si El Sayed,‘ the authoritarian father figure of The Cairo Trilogy, has become an Arabic byword for monstrous male chauvinism.

The Trilogy is universally regarded as the best epic novel ever written in Arabic. This gigantic chronicle took the form of an eyewitness review of Egypt between the two world wars in a way not seen before, marking Mahfouz’s elevation to the high priesthood of literature.

His description of Cairo and the life-style of its inhabitants proudly stands alongside those of Emile Zola’s Paris, Charles Dickens’ London and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s St Petersburg.

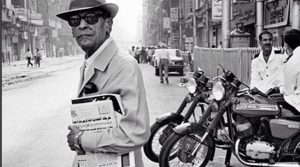

While great writers often haunt their cities, like James Joyce and Franz Kafka who remain ghostly figures on the streets of Dublin and Prague, it is Mahfouz who does the haunting in old Cairo. He himself embodied the essence of what makes the bruising, raucous, chaotic human anthill of Cairo possible. Mahfouz was, in the words of Egyptian literary specialist Dynes Johnson-Davies, ‘the perfect Egyptian gentleman’: self-effacing, tolerant to a fault, and a consummate listener. Well into his 70s he prowled far across the city on solitary early-morning walks, typically ending up in one of the many cafes where he was greeted as a returning son of the quartier. Into his 90s he rarely missed his weekly gathering of intimates at some public watering hole. There he soaked up the endless tales of woe, the political gossip and wicked jokes that provide the spice of Egyptian life.

Mahfouz never travelled abroad, even to receive the Nobel award, and hardly left the centre of the old capital. This geographical restriction was reflected in his novels. With a couple of exceptions (Autumn’s Quail and Miramar), Cairo was the setting of his muse and the arena of his characters. The details of Cairo’s vibrant alleyways and cobbled lanes jump out of the pages of his novels to invade the readers’ senses. Through his words readers can smell the frying falafel and the steaming pots of foul-medames and listen to the voices of street vendors or their imagination fantasises as his lines become a cobbled narrow alley street with the staccato clicking of an approaching stiletto of a flirtatious Cairien. The microscopic details of a way of life vanishing fast, was the trademark of Mahfouz’s craftsmanship.

Mahfouz, the youngest of seven children, was born to a local merchant’s family in 1911, in Gamaliya, one of the few old quarters of Cairo where many buildings, alleyways and souqs have miraculously escaped the savagery of modern architects; but not for long as the island of old Cairo is disappearing fast under the tide of ugly blocks which defy every urban-planning known to man. By the age of six, his father had moved the family to the modern part of Cairo, built 40 years earlier by Viceroy Ismail Pasha, who was also responsible for construction of the Cairo Royal Opera House, when Verdi’s Opera Rigoletto Was performed to mark the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Two years later opera Aida (received its first performance in Cairo ROH.

Mahfouz’s father hoped he would study medicine, but the young man chose philosophy instead, graduating from King Fuad University (later Cairo university) in 1934. Drawn to European literature, which was available in abundance, and caught up by the fashion for Egyptology, sparked by the discovery in 1922 of Tutankhamen’s intact tomb, the young Mahfouz began dabbling in writing. During last month’s quarrels with their Arab rivals, Egyptian critics, citing this information, argued that Mahfouz never studied Arabic literature by classic Arab writers, removing him even more determinedly from the ‘Arab’ writer genre. When I asked him in 1988 who were his models, Mahfouz readily admitted: “George Bernard Shaw, Gustave Flaubert, Emile Zola, Honore de Balzac, Albert Camus, Leo Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.”

Mahfouz’s formative years coincided with the era of Nahdat Misr, the renaissance of Egypt; an age of enlightenment and reason and a flourishing feminist movement. Egyptian nationalism peaked in 1922, with independence from the Ottoman empire and a national call for a return to Egyptian Pharaonic roots was promoted by the generation of effendis or perfect gentlemen, who frequented the Parisian-style cafes and literary salons of Cairo. By the mid-1940s, Mahfouz, the perfect Egyptian effendi, had published three historical novels set in ancient Egypt: Mocker of the Fates, Rhadopis of Nubia and The Struggle of Thebis.

The mature novel as a literary expression was not known in the Arabic language before Egyptian writer Dr Hussein Hykal’s 1913 novel Zynab. Mahfouz developed this form in the Arabic language, but his vocabulary was peculiarly Nilotic Egyptian and his works were full of Hellenistic, Coptic, Fatimiade and European details, embracing all post-Pharaonic foreign cultures introduced into the Nile valley, and interwoven, over 23 centuries, into the fabric of contemporary Egyptian life.

While other neighbouring cultures like the Arabs or the Levantines may have valued a warrior or a merchant in years gone by, the Egyptian civilisation, 7000 years ago as now, affords the highest social status to a ‘scribe’, and with the passing of Naguib Mafouz there is no doubt Cairo has lost one of its very finest.